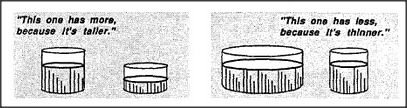

Let's try to explain the water jar experiment in terms of how a child's agencies deal with comparisons. Suppose the child begins with only three agents:

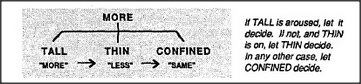

Tall says, The taller, the more. There's more inside a taller thing. Thin says, The thinner, the less. There's less inside a thinner thing. Confined says, The same, because nothing was added or removed.

How do we know children have agents like these? We can be sure that younger children have agencies like Tall and Thin because they all can make these judgments:

It is harder to know whether younger children have agents like Confined, but many of them can indeed explain that something remains the same when one pours a liquid back and forth. In any case, there is a conflict because the three agents give three different answers — more, less, and same! What could be done to settle this? The simplest theory is that the younger children have placed their agents in some order of priority.

Such a scheme can be extremely practical, since placing all the agents in order of priority makes it easy to know which to use. For example, we often compare things by their extents — by how far they reach in space. But why put Tall ahead of Wide? People do indeed seem most sensitive to vertical extents. We do not know whether this is built from the start into our brains, but in any case, the bias is usually justified because more height so frequently goes along with other sorts of largenesses.

Who's bigger — you or your cousin? Stand back to back! Who's the strongest? Those adults looming way above! How to divide a liquid into equal portions? Match the levels!

No other agent seems so good as Tall for making everyday comparisons. Still, no priority-scheme will always work. In the situation of the water jar experiment, Confined ought to come first, but the younger child's priorities lead to making the wrong judgment. One might wonder, incidentally, whether Tall and Short, or Wide and Thin, should be considered to be different agents. Logically, just one of each pair would suffice. But I doubt that in the brain it would suffice to represent Short by the mere inactivity of Tall. To adults these are opposites, but children do not work so logically. One child I knew insisted that knife was the opposite of fork, but that fork was the opposite of spoon. Water was the opposite of milk. As for the opposite of opposite, that child considered this to be too foolish to discuss.