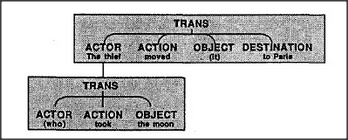

We've seen how a four-word sentence such as Round squares steal honestly could be made to fit a certain four-terminal frame. But what about a sentence like The thief who took the moon moved it to Paris? It would be dreadful if we had to learn a new and special ten-word frame for each particular type of ten-word string! Clearly we don't do any such thing. Instead, we use the pronoun who to make the listener find and fill a second frame. This suggests a multistage theory. In the earliest stages of learning to speak, we simply fill the terminals of word-string frames with nemes for words. Then, later, we learn to fill those terminals with other filled-in language-frames. For example, we can describe our moon sentence as based on a top-level Trans-frame for move whose Actor terminal contains a second Trans-frame for took:

Using frames this way simplifies the job of learning to speak by reducing the number of different kinds of frames we have to learn. But it makes language learning harder, too, because we have to learn to work with several frames at once.

How do we know which terminals to fill with which words? It isn't so hard to deal with red, round, thin-peeled fruit, since each such property involves a different agency. But that won't work for Mary loves Jack, since Jack loves Mary has the very same words, and only their order indicates their different roles. Each child must learn how the order of words affects which terminal each phrase should fill. As it happens, English applies the same policy both to Mary loves Jack and to our moon sentence:

Assign the Actor pronome to the phrase before the verb. Assign the Object pronome to the phrase after the verb.

The policies for assigning phrases to pronomes vary from one language to another. The word order for Actor and Object is less constrained in Latin than in English, because in Latin those roles can be specified by altering the nouns themselves. In both languages we often indicate which words should be assigned to other pronome roles by using specific prepositions like for, by, and with. In many cases, different verb types use the same prepositions to indicate the use of different pronomes. At first such usages may seem to be arbitrary, but they frequently encode important systematic metaphors; in section 21.2 we saw how from and to are used to make analogies between space and time. How did our language- forms evolve? We have no record of their earliest forms,

but they surely were affected at every stage by the kinds of questions and problems that seemed important at the time. The features of present-day languages may still contain some clues about our ancestors' concerns.